It took eight years to build 30 MW of offshore wind in U.S. coastal waters but the Obama administration is now pushing federal agencies to support a build of 22 GW by 2030 and 86 GW by 2050.

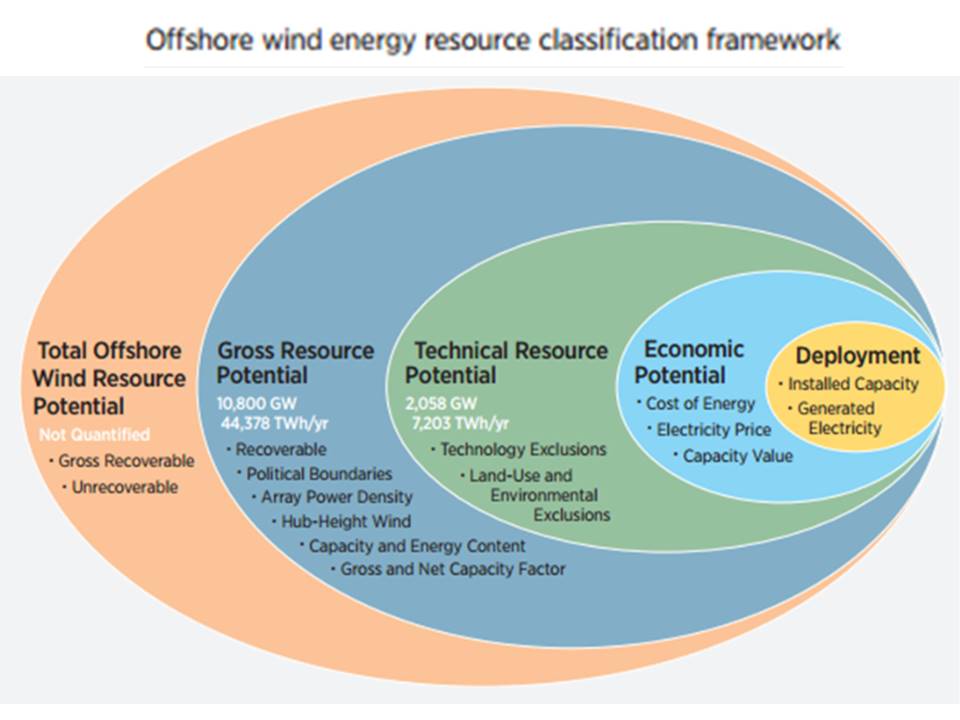

There is no doubt the potential is there. With turbine technologies now in use in Europe, U.S. coastal waters have a technical offshore wind capacity potential of 2,058 GW, which could produce 7,200 TWh per year, almost twice the total 2015 U.S. electricity generation, according to the just-updated National Offshore Wind Strategy report from the Departments of Energy (DOE) and Interior (DOI).

While reaching that total technical potential is unlikely, policy actions described in the paper can help streamline the development of the 14.6 GW of possible capacity in offshore tracts already leased by Interior, Director Abigail Hopper of DOI’s Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) told Utility Dive.

Those policy actions could also help drive the already-falling cost of offshore wind to below $100/MWh at some U.S. coastal sites by 2025 and at many more sites by 2030, added Jose Zayas, Director of DOE’s Wind Energy Technologies Office.

With policy to support the first tranche of growth that is already in the pipeline and the increasingly affordable economics that scaling would deliver, the offshore sector would be on its way toward 86 GW of installed capacity by 2050.

That build-out would produce a 1.8% reduction in cumulative greenhouse gas emissions compared to the current U.S. power mix. That would save “$50 billion in avoided global damages,” the DOE/DOI paper reports. Decreased air pollution “could save $2 billion in avoided mortality, morbidity, and economic damages.” It would reduce electric generation water use 5% and smooth the electricity price volatility created by fossil fuel-generated power.

Finally, the paper adds, “deployment could support $440 million in annual lease payments into the U.S. Treasury and approximately $680 million in annual property tax payments, as well as support approximately 160,000 gross jobs in coastal regions and around the country.”

The many policy actions detailed in the report are the path to these benefits, Zayas and Hopper stressed. They are designed to drive down costs, support technology innovation, advance site selection, and make development both streamlined and responsible.

The paper describes that kind of development as “effective stewardship of the nation’s ocean resources,” said American Wind Energy Association (AWEA) Manager of Advocacy and Federal Legislative Affairs Nancy Sopko.

It will come through policies that give offshore wind developers “certainty” as they confront the challenges of regulatory and environmental compliance, she added.

Driving down costs, supporting innovation

“Offshore wind is just a large infrastructure project in the ocean,” Hopper said. “You have to solve for several different things.”

To date, BOEM’s primary focus has been designating Wind Energy Areas (WEAs) that agency studies have identified as ripe for development, she said. DOE research has shown them to be resource rich and DOI work has shown them to hold fewer potential conflicts over commercial or military uses or environmental or viewshed concerns.

“We do not issue permits for offshore wind in places where there could be conflicts,” Hopper said. “We want to de-conflict.”

Currently, BOEM-approved leaseholders are doing survey work and site assessments, but soon the agency’s focus will shift to the evaluation of developers’ “construction and operations plans,” she said. “They can’t build it until we approve it.”

Many of the strategies in the document have to do with “accelerating and de-risking projects,” she explained. DOE is doing that for technologies through its demonstration project investments. DOI is doing it by building “a predictable regulatory scheme” with “as little risk as possible” for developers and their financiers.

The de-risking of the regulatory regime is high on the federal agencies’ agendas because U.S. financial institutions have remained largely on the sidelines in the offshore sector due to risk.

“But European financial institutions have begun to show interest and we expect domestic parties to follow,” Zayas said.

In Europe, where there are already 12 GW of installed capacity, cost trajectories are coming down faster than forecasts, Zayas said. Both DONG Energy and Vattenfall are now developing offshore projects in the North Sea with “all-in costs, including transmission, of less than 10 euro cents per kWh or 11 U.S. cents per kWh.”

The paper’s $100/MWh by 2030 forecast for both fixed and floating foundation turbines aligns with those European costs, Zayas said. The paper also describes anticipated capital expenditure reductions from technology innovations that produce higher capacity factors and lower installation, operations, and maintenance (IO&M) costs.

The now-mature fixed foundation technologies are expected to be $93/MWh in 2030, according to the paper.

Thanks to significantly lower IO&M costs, floating foundation technologies are expected to be $89/MWh by then. That will open to development the 58% of the U.S. technical potential in waters too deep for fixed foundations.

“That is a big prize,” Zayas said. The department is committed to floating technology because we think it is a place where the U.S. can lead and contribute on a global scale.”

Three DOE-funded Advanced Technology Demonstration Projects, off the Atlantic coasts of Maine and New Jersey and off Ohio’s Lake Erie coast, are expected to speed the falling cost trajectory, the paper reports. The Maine project has a floating foundation.

In addition to the specific technology advances, other innovators will be able to build on data from the demonstrations when it is made public.

“Another attribute of offshore wind is that it is close to the large load centers,” Zayas said. “The U.S. onshore resource is at a distance from those load centers and it is either cost- or time-prohibitive to wait for transmission expansion."

The "mismatch" between generation and transmission development means it may soon be more cost-effective to build and deliver offshore wind than to move power to load centers from wind farms in the center of the country, he added. “That is a value proposition.”

Another value proposition is that offshore wind is “more aligned with load patterns,” Zayas said. “People use electricity in the morning and the evening. Onshore winds are often strong at night. Typically, offshore winds tend to be steadier and more available during the late afternoon and early evening peak demand periods."

Different solutions will work along different coasts at different adoption rates, he said. Because of its high electricity prices, “the northeast will probably be the incubator of innovation.”

Floating foundation technology is “the only game in town for the West Coast and Hawaii” because of how deep even near-shore waters are there, Zayas added. But adoption may be delayed until the technology comes down the cost curve.

Utilities testing the water

Utilities have just begun to wade into ocean wind. Although National Grid and Eversource backed out of their power purchase agreements (PPAs) with the controversial Cape Wind project, Massachusetts’ just enacted 1,600 MW offshore wind mandate by 2027 that will require both utilities to immerse themselves.

National Grid and the Block Island Power Company have been good partners in the Block Island project, the first U.S. offshore installation, AWEA’s Sopko said. But the new Massachusetts law is “an industry-maker.” National Grid and Eversource "must fill out the first of four 400 MW capacity tranches by July 2017.”

Cleveland Public Power has committed to act as off-taker for 25% of a project on Lake Erie when it goes online, she added. “Utilities should be aware that offshore wind is a great opportunity to diversify the grid and provide ratepayers with clean abundant energy that is close to the largest population centers.”

Dominion Virginia Power’s offshore pilot proposal was an early DOE demonstration project awardee. It was replaced in the second funding round when the project failed to meet department criteria and the utility’s board did not provide an off-take agreement, Zayas said. The estimated higher-than-market price for the pilot’s generation may have been a factor, he added.

“Off-take is the hardest part of an offshore wind project right now, especially when the price is above-market,” he added.

The Massachusetts mandate is a use of “the legislative path” to overcome the price barrier. Other early adopters will likely be in places like Hawaii where the electricity price averages the highest in the nation.

On the other hand, Dominion continues to hold the lease it won in an early BOEM auction, Zayas said. “They still seem to be interested in offshore wind because they are holding on to that lease.”

Offshore wind is not a “one-size-fits-all solution” for utilities but they “have a really important role to play,” Hopper said.

For many, the cost is at present difficult to justify to their regulators, she acknowledged. But the cost curve has “changed dramatically over a very short period of time,” she added.

Until there is more U.S. offshore wind installed, the price an experienced developer can deliver it at will not be clear, she said. “But there is more to come on the question of cost.”

It is one thing to get energy that creates a lot of carbon pollution at a very low per-kWh rate, but another to get energy that is priced fairly for accommodating the Clean Power Plan and other pollution reduction commitments the country has made, she said.

“Our state commissions have a lot of interesting conversations ahead of them about what ‘just and reasonable’ means as energy markets change,” Hooper said.

In a decade's time, the feds expect most offshore lease tracts around the U.S. will be quite competitive with traditional generation.

Effective stewardship through streamlined permitting

The most important part of the strategy paper may be its 34 action items in seven areas that DOE and DOI can take to balance growth with other concerns, Sopko said.

“We want to promote the technologies but we want them to co-exist with environmental conditions and human-based uses,” Zayas said. “Those are areas where agencies and the industry must work together.”

The 34 actions, drawn from DOE and DOI outreach for stakeholder and public input, are largely aimed at streamlining the development process, Sopko said. “The regulatory process for Block Island took eight years and it’s only a 30 MW project. To build a thriving industry, that timeline needs to be cut down.”

Offshore wind is new, Hopper said. Land-based wind developers have worked out many of the permitting challenges with the governing agencies. BOEM’s goal is to provide the most reliable, predictable regulatory construct possible.

“Obviously building something in the middle of the ocean represents more engineering challenges but the difficulties with permitting have more to do with the newness of the technology,” she added. “Several developers told us the process through which we identified and leased the wind energy areas has been efficient. We want the plan approval process to be equally effective."

“This national strategy paper is a great roadmap to “effective stewardship,” Sopko said.

Dong Energy, the world’s largest offshore wind developer, agreed. The National Offshore Wind Strategy report “represents an important step in the development of clean, cost-effective offshore wind power in the United States,” U.S. Wind Power General Manager Thomas Brostrom told Utility Dive. "It is a positive step towards helping to meet the country’s growing energy needs.”

Stewardship that is “effective” provides rules that allow “responsible development,” the paper reports. Actions are needed now to ensure “efficiency, consistency, and clarity in the regulatory process” by “providing more predictable review timelines.”

BOEM can speed environmental reviews by collating more data about offshore wind’s impacts on human uses and sensitive biological resources, the paper reports. Resolved issues could be retired, allowing “a greater focus on the most significant risks and impacts.”

More certainty in construction and operations plan reviews would be another important step toward “getting more projects in the water as quickly as possible,” Sopko said. The current lack of definite timelines for federal agency reviews “creates a snowball effect” when investors become dissatisfied about development delays and abandon developers, she added.

An important streamlining of the plan review could come from using the “design envelope” approach used in European offshore wind. It would add flexibility by allowing developers “to make final design decisions later in the process and take advantage of emerging technological improvements,” the strategy paper reports.

“BOEM would create an ‘envelope’ for the Environmental Impact Statement and the project plan would have to be within the envelope's general parameters,” Sopko said. “Developers could then defer project design decisions that might be more cost-effective later in the permitting process.”

Moving ahead

Cooperation between DOE and DOI has been effective because each agency brings a different kind of expertise and focus, making “the sum better than the parts,” Hopper said.

But the offshore industry needs to be ready to step up its game, she added.

“Our climate is changing rapidly and there is an increasingly urgent need to rethink how we fuel our economy and to act on alternative energy sources,” Hopper said. “Our nation has begun well with land-based wind and solar and offshore wind is another incredibly abundant resource close to load that we are now ready to make use of.”

Jeffrey Grybowski, CEO of Block Island developer Deepwater Wind, agreed. "We are convinced that offshore wind will be a major contributor to the nation’s clean energy supply in the coming years,” he told Utility Dive. “Electric markets in the Northeast will be the first to see a major supply of offshore wind come online in the early 2020s.”

“We have a couple of site assessment plans, which is the first stage of our permitting process, under review now,” Hopper said. “This is the beginning of a process of timely and predictable review.”

The goal is not just the approval of the projects under scrutiny but the building of “a robust and cost-competitive new energy industry,” she added.