FERC’s proposal to reform transmission planning has provoked a confrontation over federal and state control of transmission expansion, prompting some stakeholders to call for new oversight.

But U.S. transmission’s 1% annual growth must more than double to an average of about 2.3% to meet federal climate goals, according to Princeton University’s September report, Electricity Transmission is Key to Unlock the Full Potential of the Inflation Reduction Act. With hundreds of billions in largely ratepayer dollars for transmission at stake, and potentially much more as climate crisis-driven extreme events worsen, proposed solutions to accelerate transmission building by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission have sparked debate.

FERC wants “to socialize the costs” of a “massive transmission build-out” for what many see as “an aspirational renewable future,” Commissioner James Danly, appointed by President Trump, said, adding that decisions on transmission are best made by the states hosting it. FERC is “not the Good Ideas Commission,” and its “pervasive, and invasive ‘reforms’” are “unjust and unreasonable,” and will lead to “protracted proceedings, litigation, and risk,” he wrote.

The FERC proceeding filings show “the electric system needs to evolve” to benefit regions and the U.S. climate fight, responded former FERC Commissioner John Norris, a President Obama appointee. “The economy has evolved into an international market, but too much power remains with local utilities to maximize their own assets’ value instead of building a more efficient system,” he said.

New transmission is vital to the cost-effectiveness of federal plans for clean energy investments, Utility Dive recently reported. With a Senate permitting law now in doubt, FERC reform of planning factors like who benefits, who builds, who pays, and who does oversight is urgently needed to resolve impediments to development, stakeholders agreed – without agreeing on which reforms will work.

FERC’s proposal

FERC’s Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, or NOPR, seeks “forward-looking” long-term regional transmission planning, it announced April 21. With generation and load now including growing penetrations of renewables and storage, and greater distribution system electrification, transmission planners need to use multiple scenarios that look out “at least 20 years” and are “updated every three years,” it said.

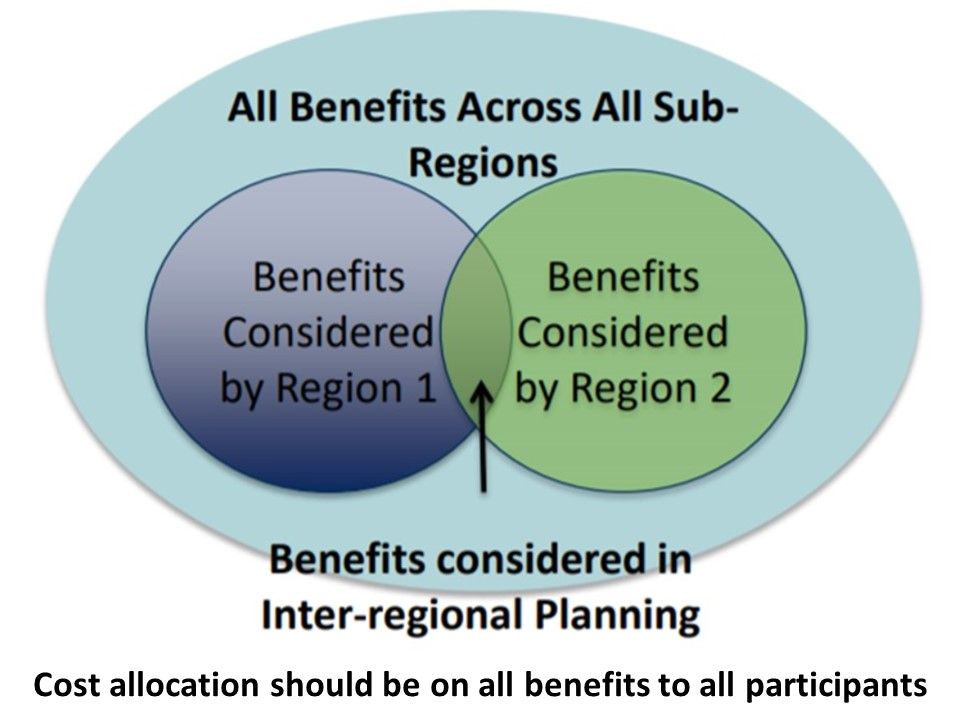

FERC also seeks streamlined coordination in regional and local transmission planning and interregional planning that allocates development costs among states using all benefits to ratepayers, the NOPR added.

Finally, utilities’ right of first refusal, or ROFR, which is a first option to build transmission projects in their service territories, would be conditionally restored after being curtailed by 2011’s FERC Order 1000. That would limit the competition for transmission building sought by Order 1000, but it might streamline needed development, FERC said.

Without these reforms, planners could fail to consider valuable approaches to building transmission that reflect state input and limit ratepayer costs, FERC said.

But regional and state entities can and should identify their own reforms, Commissioner Danly wrote. The NOPR’s “narrow environmental policy objectives” fail “to clarify the single most critical question,” which is why customers in states without climate policies should pay for transmission in neighboring states with those policies, Danly wrote.

Stakeholders want guidance from FERC, he acknowledged. But the NOPR proposals could “stifle” innovation, least-cost solutions, and investments, he warned.

The flexible use of benefits to allocate costs by the Midcontinent Independent System Operator, or MISO, for its recently approved $10.5 billion Transmission Expansion Plans, or MTEPs, may be a solution, many stakeholders said.

Flexibility?

FERC’s NOPR offered 12 transmission benefits that can reduce debates over allocating costs among states. Its “avoided or deferred reliability” led the list, which also included cost-reduction benefits and more cost-effective capacity or reserves. It ended with transmission’s benefits of “access to lower-cost generation,” and “increased competition.”

But FERC’s approach has “a central defect,” a joint filing by environmental and reform advocates responded. Without better “benefit assessments,” unrecognized benefits could lead to “poorly targeted transmission investments,” they said.

ITC Holdings Corp. Senior VP and Chief Business Officer Krista Tanner disagreed. To drive regional transmission development, “FERC should establish core benefits like those used by MISO while avoiding too many required benefits, which would discourage building,” she said.

Prioritizing benefits like “avoided generation and fuel costs, avoided congestion, avoided transmission investments, resource adequacy savings, and decarbonization,” would accelerate development, she added.

“Flexibility,” or even “more than one cost allocation methodology,” helps avoid disputes by recognizing states’ “policy diversity,” and “existing processes,” MISO’s filing agreed.

MISO’s 2011 and 2022 MTEP portfolios did not calculate benefits in detail, Brattle Principal Johannes Pfeifenberger said. Instead, they accurately showed broadly that “benefits would exceed costs” across participating states, and that broader approach led to transmission investments that, even if not needed for reliability, will “reduce overall costs and customer rates,” his filing showed.

Grid Strategies founder and President Rob Gramlich, a former FERC staffer, captured the subtle difference between parties over the ROFR’s proposed benefits. “FERC’s list of benefits is generally sound,” and the key question is whether any proposed benefit “can be ignored,” he said.

The difficulty is that some benefits on FERC’s list are “hard to quantify” and “controversial,” the Edison Electric Institute filing for its investor-owned utility members said.

But because debating benefits has been used by some incumbent utilities to stall and delay when they see no self-interest in allowing projects built by independent developers to go forward, any commitments by those utilities toward compromise on benefits in this proceeding “could move it forward,” former FERC Commissioner Norris added.

Moving reforms forward will, however, face one of the biggest questions FERC has seen over most of this century in efforts to expand transmission — competition.

Competition?

Order 1000 was a bipartisan effort, said Jon Wellinghoff, the Obama-appointed FERC Chair who led its 2011 approval after decades of debate and enactment of the enabling 2005 Energy Policy Act under Republican President George Bush.

But the cost-effectiveness of the competitive solicitations Order 1000 requires has been challenged by an August Concentric Energy Advisors study.

“Completed and active competitive transmission projects awarded to non-incumbent developers experienced an average of 12 months in schedule delays and 27% in cost increases” over their bids, according to an Aug. 16 press release from ITC Holdings Corp.

“It is not evident that lower costs and greater innovation have been realized on a broad scale through the implementation of Order 1000. In fact, project selection criteria that emphasize low costs may run counter to the goals of innovation via new solutions,” according to Concentric.

Those findings may suggest “non-incumbent entities” are focused on winning the competition rather than making “realistic bids,” according to the Concentric study.

MISO’s successful 2011 transmission expansion, approved before Order 1000’s passage, showed competition in MISO “was never needed,” the MISO Transmission Owners Sept. 19 filing in the FERC NOPR proceeding added.

But “without competition, incumbent utilities have no reason to provide the best outcome for the consumer,” former FERC Commissioner Norris responded.

Others also question Concentric’s conclusions.

Concentric’s study is based on the “about 2% of all transmission built in the last decade through competitive solicitations,” and “when there is not much competition, there is not much benefit,” Brattle’s Pfeifenberger said. A Brattle 2019 study showed average incumbent costs for new transmission development were 30% above the initial estimates made by those incumbents, which were about 20% above competitive bids, he added.

Concentric reported cost proposals from incumbent utilities ranged “from approximately $100 million to $1.55 billion,” LS Power Development President Paul Thessen said in August 2022 testimony in the NPOR proceeding. Without competing alternatives, those bids could have cost ratepayers an additional “hundreds of millions to over a billion dollars,” he said.

Former PJM VP of Planning Steven Herling, now a power system consultant, disagreed. Both “are representing their own financial interests with equal biases,” he said. Competition may offer “cost containment in new transmission,” but “most transmission spending is for infrastructure upgrades that would be difficult for non-incumbents to do cost-effectively,” he added.

As renewables generation grows, there will be “big opportunities for innovative, cost-competitive regional and local transmission developers,” he said. “FERC needs to find a compromise solution to allow all transmission development to move ahead,” he urged.

The competition issue “is being fought by litigious people who care a great deal about their business models,” Grid Strategies’ Gramlich said. FERC’s focus is not “any one business model,” but “getting needed infrastructure built,” he added.

The NOPR-proposed conditional ROFR for incumbent utilities, though inadequate to fully restore competition, may be a compromise path forward, EEI’s filing said.

Also looking to reduce “the tension and uncertainty” of current planning, MISO’s filing proposed an alternative “default” ROFR allowing states to “opt in” to competitive regional transmission development. Making it optional would respect states’ authority over local development, MISO said. But “any ROFR reform should facilitate cooperation,” and ensure “regional projects get timely built,” it stressed.

Reducing uncertainty about the many details of transmission development, like bids and costs, and improving cooperation between stakeholders with vested interests in development was the objective of new regulatory oversight urged by some stakeholders.

Oversight by regulators’ “eyes and ears”

“Gaps” in available information may prevent identifying the best protections for customers and ensuring the most affordable and reliable choices by regulators, FERC Chair Richard Glick said to conclude an Oct. 6 FERC transmission planning conference in which many stakeholders endorsed an Independent Transmission Monitor, or ITM.

ITMs would “oversee transmission planning regulation compliance and have access to all information necessary for reporting purposes, just as Independent Market Monitors, or IMMs, do for markets,” former FERC Chair Wellinghoff told Utility Dive.

IMMs show FERC’s jurisdiction for establishing ITMs, which could similarly “bring public and commission attention and pressure” where compliance is questionable, he said. Oversight might have brought earlier notice that avoided today’s interconnection queue backlogs or more clarity to incumbent utilities’ role in the limited success of Order 1000’s competition mandate, he added.

But an ITM is unnecessary in regional organizations, both MISO and PJM filings said. Without evidence that regional organizations are not meeting FERC requirements to plan “in a just, reasonable and not unduly discriminatory or preferential manner,” disputes should be left to regional organizations’ resolution processes, PJM insisted.

ITC’s Tanner agreed. “Adding bureaucracy could make building urgently needed transmission take longer and cost more,” she said.

“Incumbents might complain about added bureaucracy or find ways around it,” former FERC Commissioner Norris responded. But objective, data-based ITM reports, like those from IMMs, could give state regulators leverage against incumbent utilities’ influence, he added.

PJM IMM Monitoring Analytics’ President Joseph Bowring and Beth Garza, former director of the Texas IMM and now energy and environmental policy senior fellow for consultant R Street, agreed.

Independently funded ITMs could “be the eyes and ears of regulators,” Garza said. But only “if they have the authority” to obtain and present to regulators complete data and information on “incumbent utilities’ regulated returns and on where transmission planning is or is not conforming with FERC rules,” she stipulated.

Harvard Law School’s Electricity Law Initiative Director Ari Peskoe proposed a Ratepayer Transmission Monitor, or RTM, essentially a customer-focused ITM, in a Sept. 16 filing.

Transmission investments should be subject to a “prudence review,” and if customers and stakeholders do not get “relevant and timely information” from developers, FERC-authorized RTMs could access it, Peskoe wrote.

RTM engineers could also offer technical expertise, and RTM analysts could balance competing claims in consultant studies to “enable more robust stakeholder involvement,” he added.

But many states will not willingly “give up regulatory authority on planning,” warned former PJM planning executive Herling. “The question is whether FERC will make hard decisions to require some conformity, which it has not typically done in the past,” he said.

However, the “patchwork fixes” system operators “have been making for the last 20 years to meet the power system’s changing generation and load” need reform, Herling acknowledged. And “those changes must be comprehensive and coordinated to avoid unintended consequences,” he said.

Former Texas IMM head Garza agreed hard decisions are ahead. “The FERC proceeding is an attempt to move the imperfect world closer to the most efficient approach,” she said. “In many respects, the value is in the process.”

Observations by ITC’s Tanner demonstrated the tension. It is “disappointing that stakeholders from the competitive space oppose proposals in the NOPR,” because “we needed more transmission yesterday,” and “it takes a long time to build,” she said.

Final rulings in FERC’s several transmission proceedings may be completed by Q4 2023, with regional systems’ compliance plans filed in H1 2024, Brattle’s Pfeifenberger estimated. “Transmission planning takes two years and building transmission projects takes five to 10 years, which means new projects may be in operation by the early or late 2030s,” he said.

Correction: A previous version of this story used an incorrect abbreviation for Concentric Energy Advisors and misattributed two statements. The story has been updated.